History and care of photographic slides

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Michelle Kennedy, Manager of Collections Information and Research Services

May 25, 2023

Since the Collections Chronicles blog post series started in June 2020, there have been over 40 posts discussing a wide range of collections artifacts and the stories they can tell. When I was looking through the Collections Department’s past posts to brainstorm what I could highlight next, I noticed there was an artistic medium that had been explored more times than any other: photography. From glass plate negatives to black-and-white prints of aerial surveys, five blog posts have focused on photographic collections and more than half of the 40-ish posts have included at least one archival photograph.

Maybe I should have taken this as a sign to steer away from photographs for this post, but there is still a type of photograph that hasn’t been explored, or even mentioned. With over 33,000 photographic slides in the collections and archives, spanning from the late 19th century to the 1990s, slides actually make up the majority of photographs at the Seaport Museum (outside of digital formats).

With that in mind, this post is going to briefly talk about the history and development of slides, the heyday of the 35mm slide in the mid-to-late 20th century, and how we (and you) can take care of them for better preservation.

Top: [View of Washington Square Arch], late 19th-early 20th century. Glass positive print. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

Bottom: Arthur Dunn Cleveland (American, 1873-1956). [USS Mayflower cruising on the Hudson

What is a Slide?

Photographic slides are positive images on a transparent base like glass or plastic. This allows for the photograph to be projected onto a surface through a lens with a light source shining through it. They are called “slides” because the projectionist would physically slide each image in front of the light source; this sliding motion would later be automated using slide carousels and magazines.

The fact that early photographic slides were developed on glass means that they are sometimes confused with glass plate negatives; however, a slide is processed as a positive image, with the light and dark areas of the subject as they appeared when photographed.

Magic Lanterns

Before talking about photographic slides specifically, we should first talk about how slide projectors came to be. The earliest projectors, known as magic lanterns, date back to the 1650s—long before the discovery of photographic techniques in the 19th century. By the 1700s the magic lantern show was a form of entertainment in Europe, with projectionists often traveling between communities with a series of hand-painted slides and portable lanterns. In a time before motion-picture film, smoothly manipulating a series of transparent slides created an experience somewhere between still images and life-like motion.

Left: “Magic Lantern”, ca. 1900. Glass, tin, paint. Seamen’s Bank for Savings Collection 1991.074.0045.A-.C

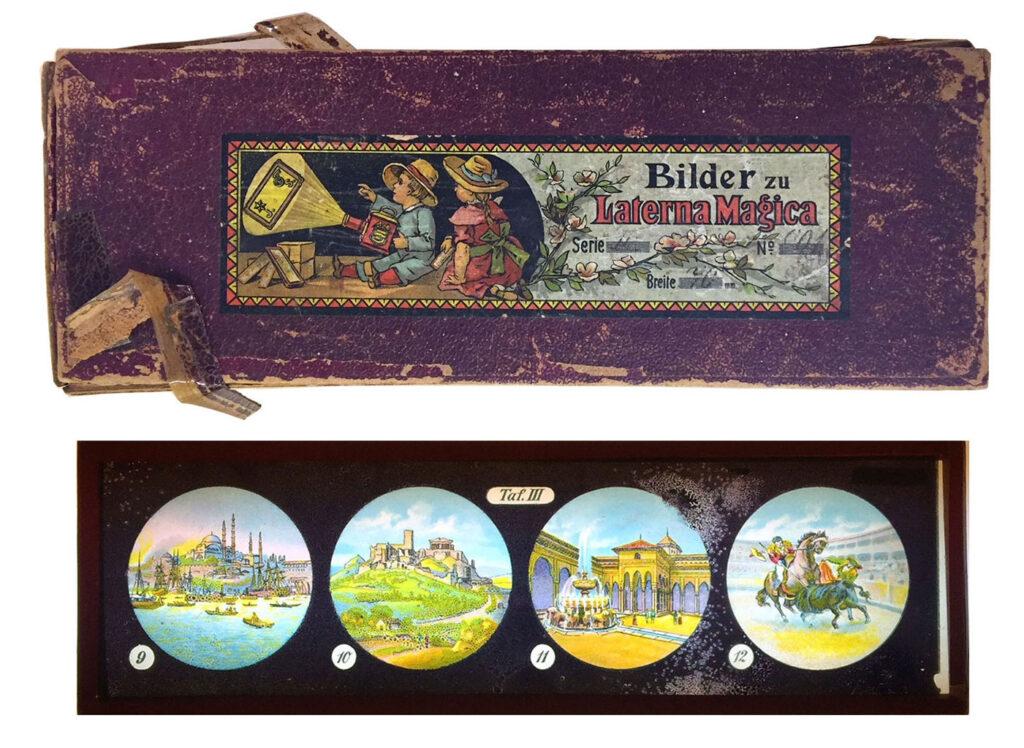

Right: Jean Schoenner, manufacturer. “Box of Magic Lantern Slides”, late 19th-early 20th century. Glass, paint, metal, cardboard. Seamen’s Bank for Savings 1991.074.0070

By the mid-to-late 1800s, magic lanterns and slide shows came into widespread use due to developments in illumination beyond candlelight, and the invention of both photographic and printing technology for creating slides. Hand-painting slides was a difficult and expensive art, so when a British manufacturing company was able to adapt chromolithography to print colorful illustrations on glass around 1870, illustrated magic lanterns slides began to be mass produced. These slide series were often marketed as toys for children, like the above example from German manufacturer Jean Schoenner (active 1875–1912).

Slides and Photography

Photographic lantern slides were first introduced in 1849 by the Langenheim brothers of Philadelphia (active 1841–1850). While toy manufacturers favored printing fanciful illustrations for their slide series, slides produced from photographs became popular for a wide variety of entertainment and educational purposes for all ages. Any subject that could be photographed could be the subject of a slide show. Slides were developed to illustrate scientific lectures, for sharing views of foreign and famous sites, and for public amusements. Many of the photographic lantern slides in the collection are actually photographic reproductions of artworks like paintings, prints, and sculptures, produced by museums for schools and libraries across the country.

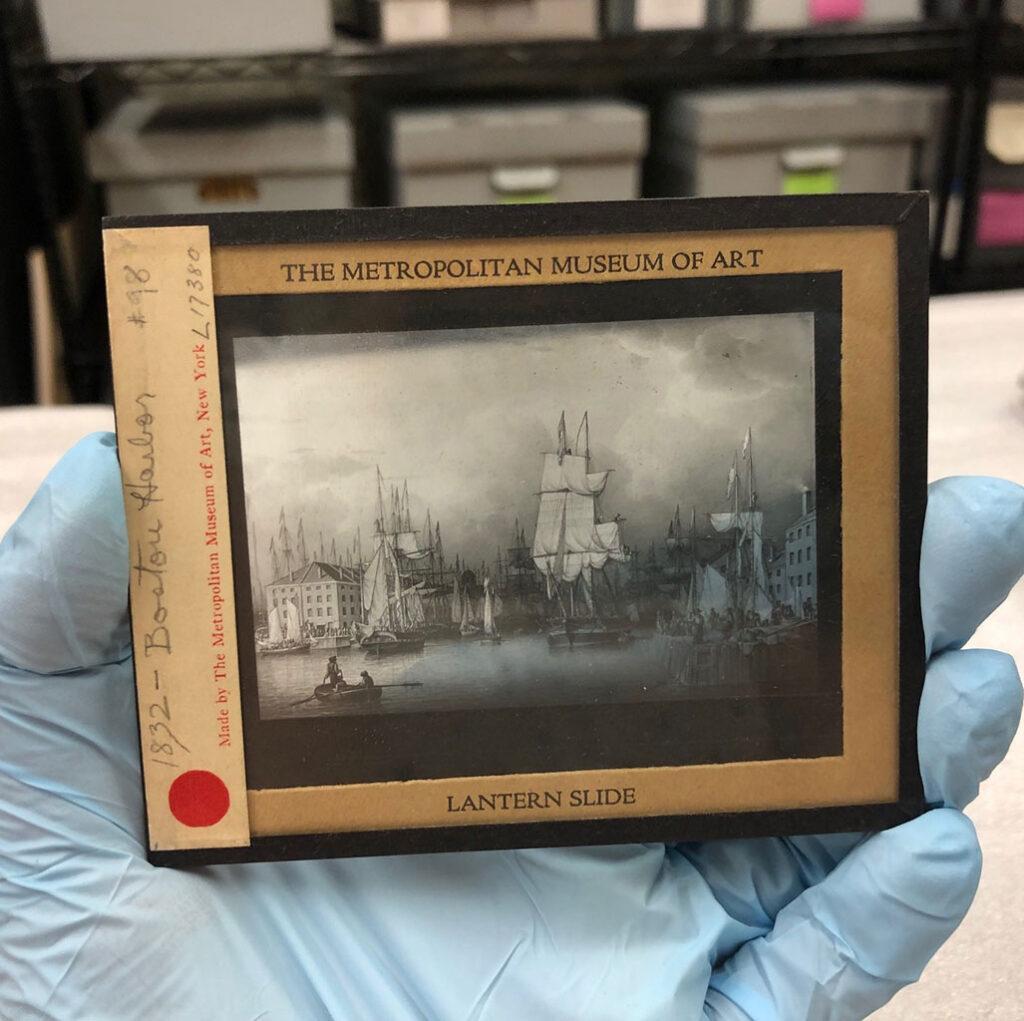

Left: Metropolitan Museum of Art, publisher. “Boston Harbor”, early 20th century. Glass positive print. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

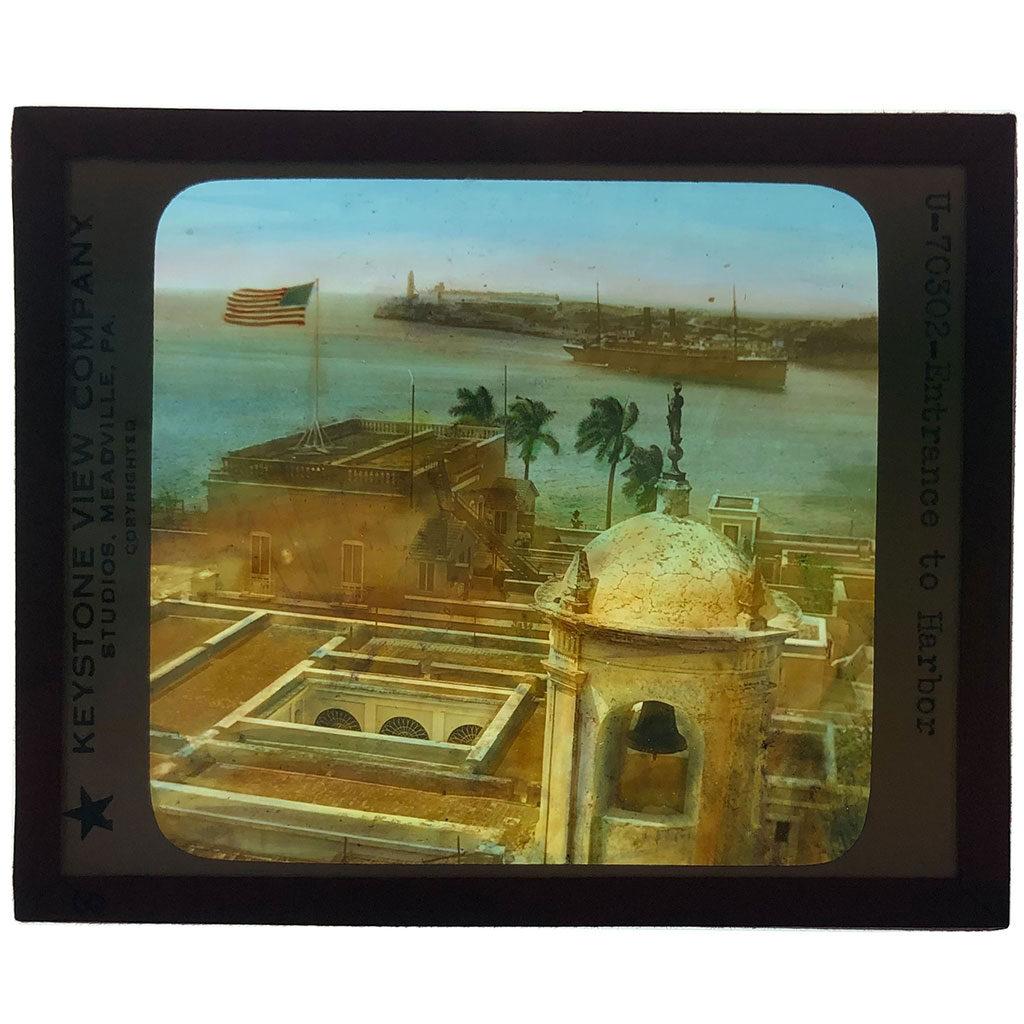

Center: Keystone View Company, publisher. “Entrance to Harbor”, late 19th-early 20th century. Hand-colored glass positive print. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

Right: A.H. Pinkney, publisher. [View of the Statue of Liberty], late 19th-early 20th century. Glass positive print. William Asadorian Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Archives

Starting in 1857, slide manufacturers used the wet plate collodion developing process, where the light-sensitive solution had to stay wet while the image was exposed. This wasn’t a problem for slide manufacturers and their labs, but it wasn’t until the gelatine dry plate process was developed in the 1870s that amateur photographers could more easily create their own photographs and slides. By the 1880s it became possible for someone to share a slide show of their vacation photographs with friends and family—an experience that became commonplace with the 35mm film slide in the mid-20th century.

Left: “East River Traffic with Fulton Ferry”, ca. 1900. Glass positive print. William Asadorian Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Archives

Center: “Puppies” late 19th-early 20th century. Glass positive print. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

Right: [Man photographing a deer in snowy woods], late 19th-early 20th century. Glass positive print. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

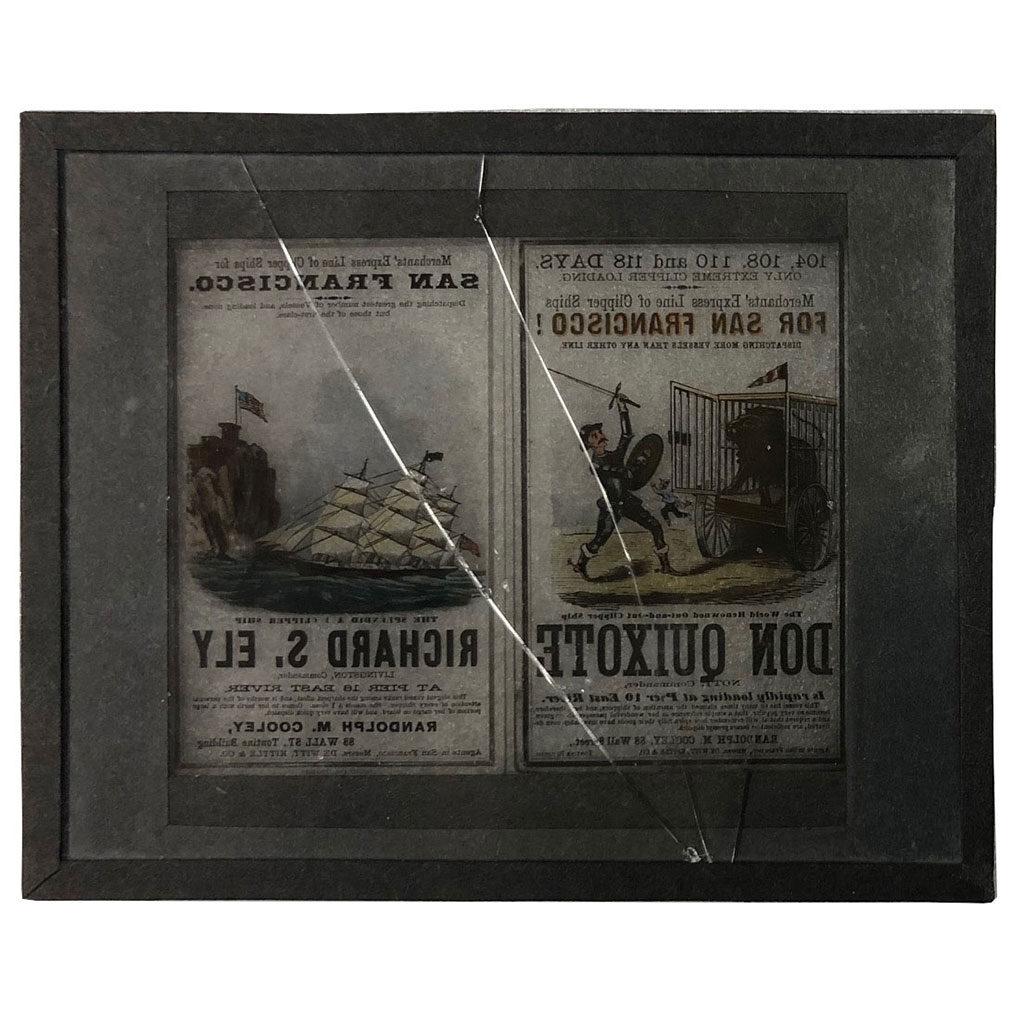

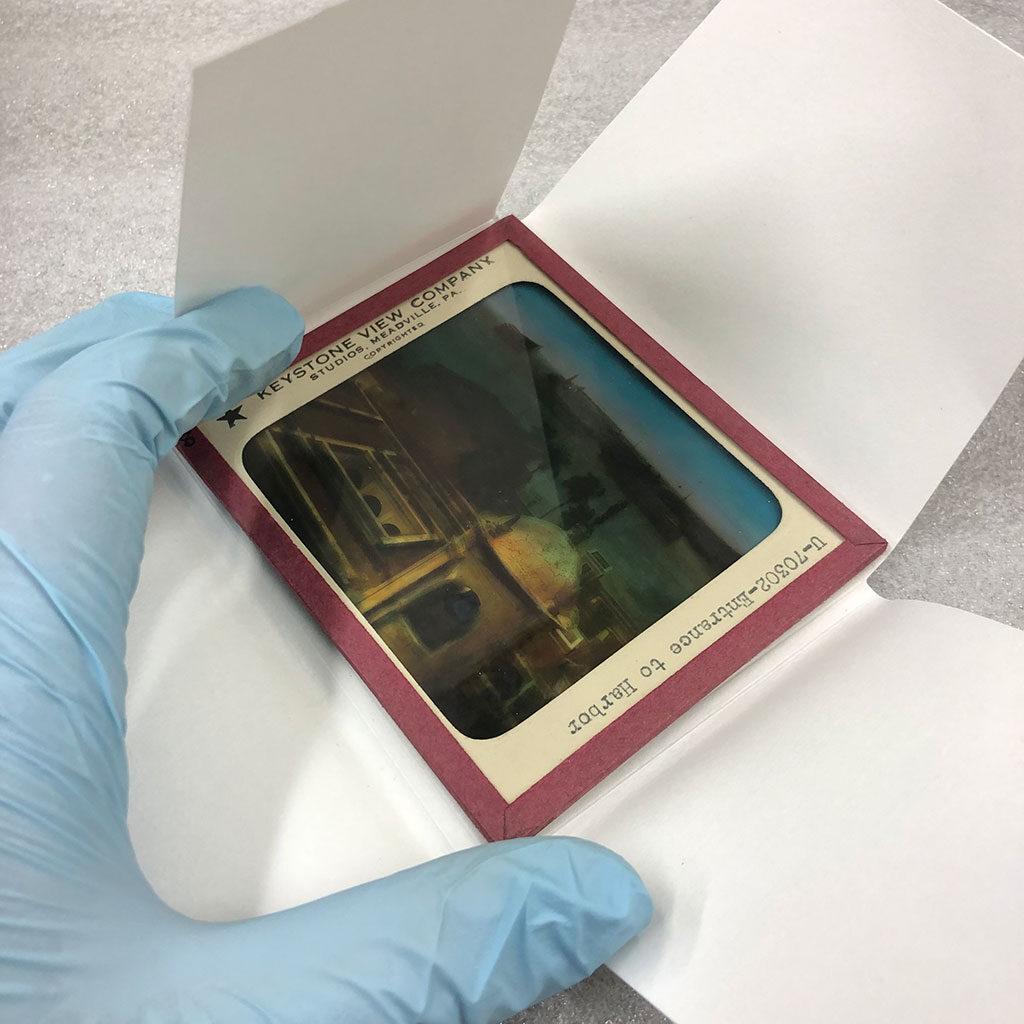

When caring for glass lantern slides (photographic, hand-painted, or printed) one of the forms of damage that can present is cracking of the glass itself. Glass is a relatively stable and durable material, especially compared to the transparent plastics used later in the 20th century, and slides were designed to be frequently handled while being projected; however, if they are stacked horizontally on top of one another without proper support, the bottom slides can crack under the weight. Additionally, though the emulsion layer of an intact slide is protected by glass, the glass itself should be protected from scratches by enclosing it in a four-flap envelope. These envelopes are also helpful to collections staff since we can easily label them in pencil.

Left: Lantern slide with cracks running across image

Center: Lantern slide being placed in a four-flap paper enclosure

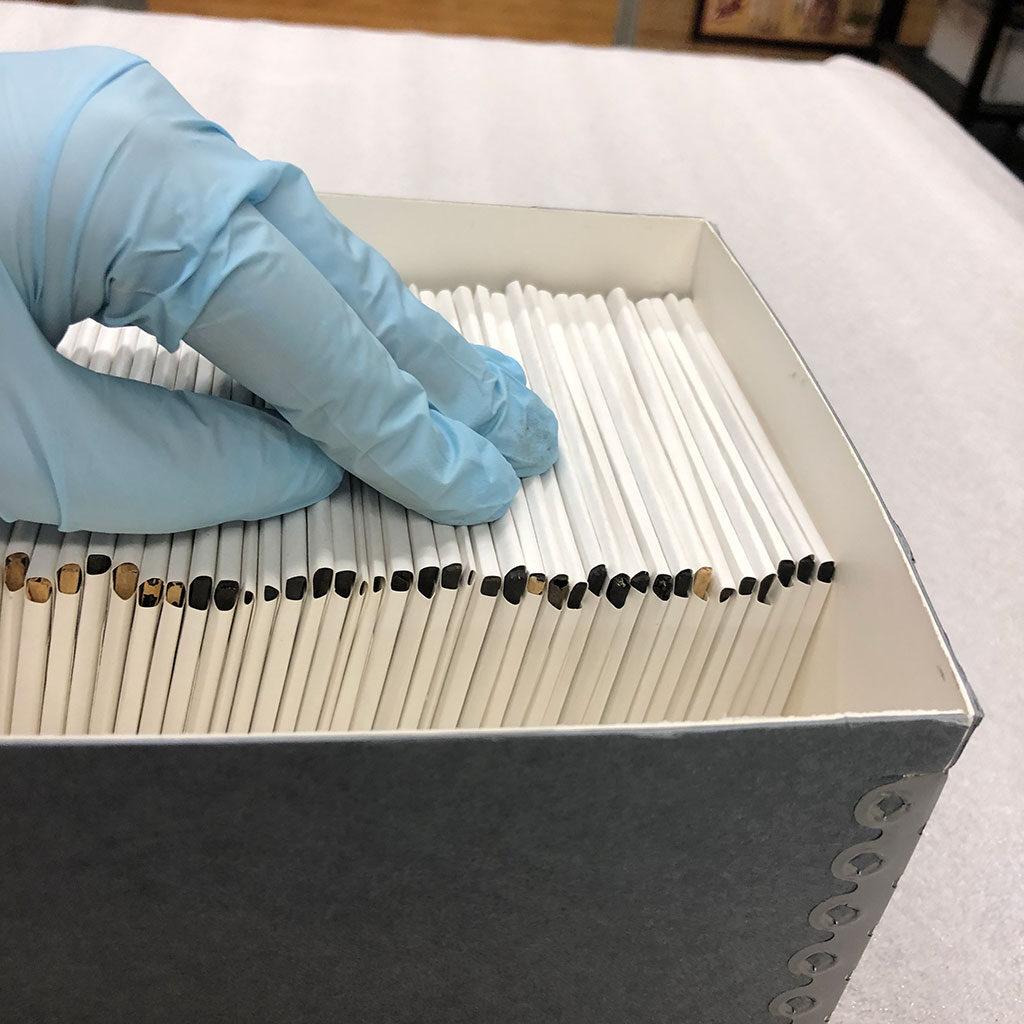

Right: Lantern slides stored upright in archival box

Rise of the 35mm Format

Glass slides would begin to be superseded by film-based slides in the mid 20th century. Though motion pictures had already long replaced public slide shows as popular entertainment, projections were still needed for schools, clubs, and business meetings. Though black-and-white slide film would be developed around 1930, a craze for slides began with the introduction of Kodak’s 35mm color slide film in 1936, based on their revolutionary 16mm three-color motion picture film released the year prior.

35mm had become a commonly produced movie film since its development in the 1890s, so it was a cost-effective film gauge to adapt to still cameras. Though there is a lot of interesting science about the chemical processes used for Kodachrome and the other color slide films developed in the following decades (like Ektachrome, Fujichrome, Ansco color film among others), it is a bit much to get into here!

To summarize, a color 35mm slide consists of chromogenic dyes on a piece of transparent film which is then framed in a plastic or cardboard mount. These mounts are what give the flexible film enough stiffness to be slid into a projector when viewed.

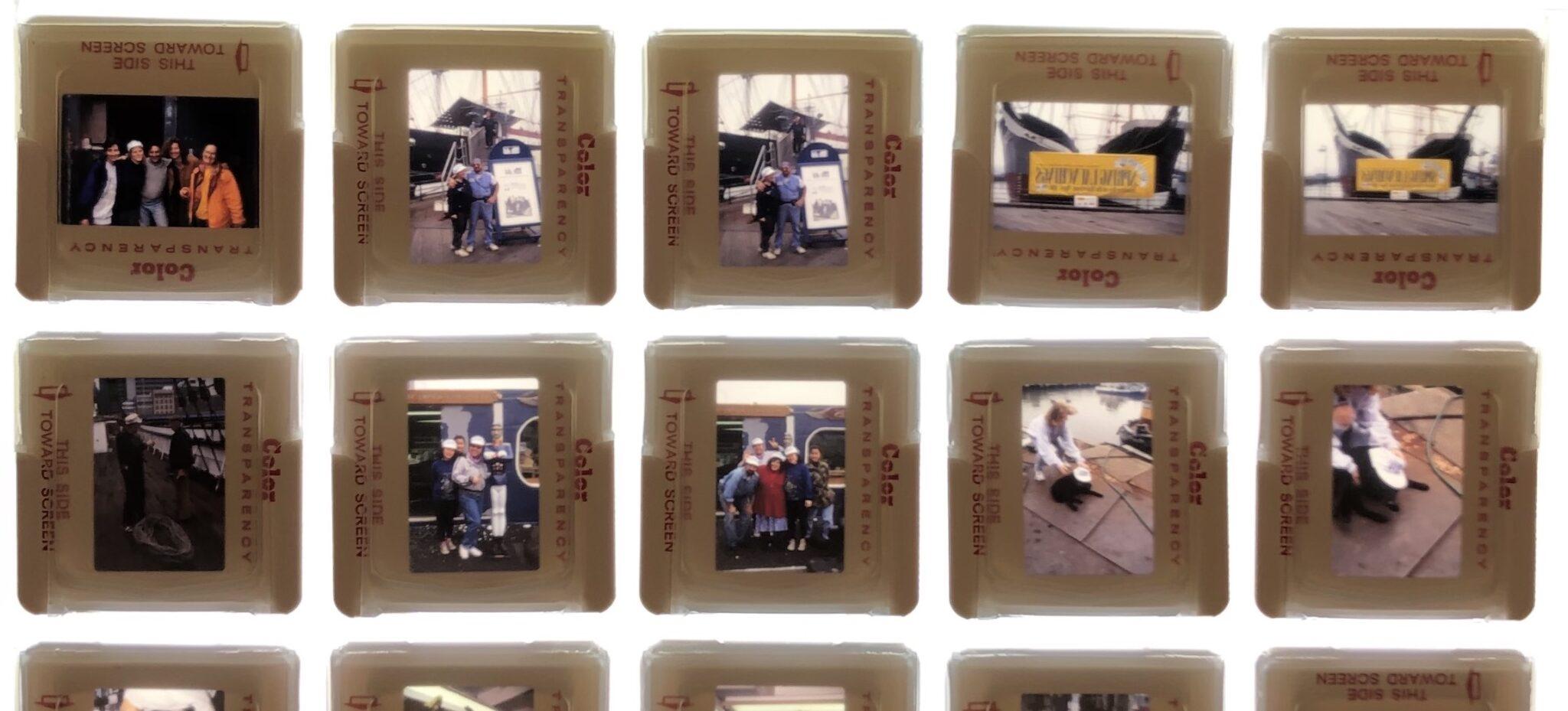

35mm color film slides being viewed with a light box

Film slides like those made by Kodak offered a lot of advantages. Lighter and smaller than glass slides, 35mm slides are easily stored, moved, or even sent through the mail. They are incredibly high-resolution, retaining their sharpness and detail when greatly magnified while projected. The color reproduction for many films were excellent. Most importantly, 35mm slides were relatively cheap and accessible compared to other options for high-quality color photography.

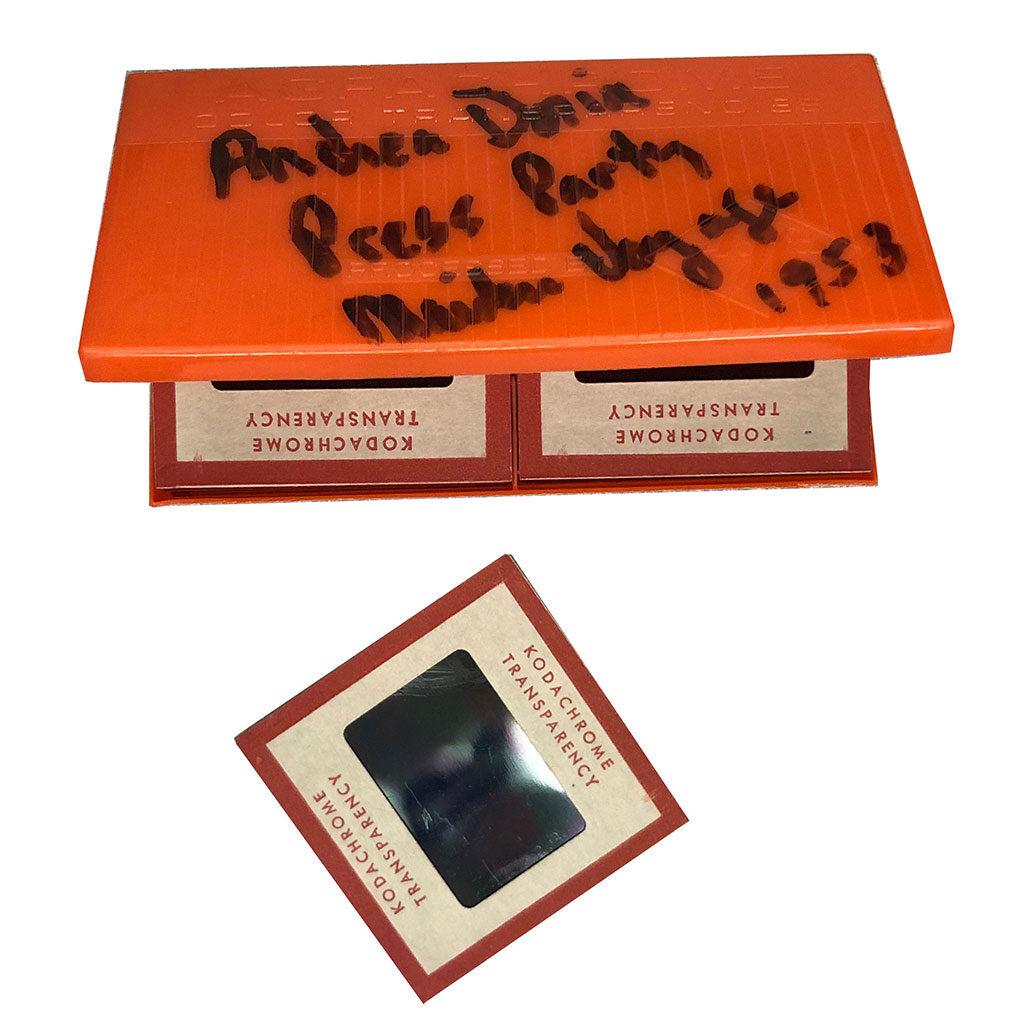

Slides at the Museum

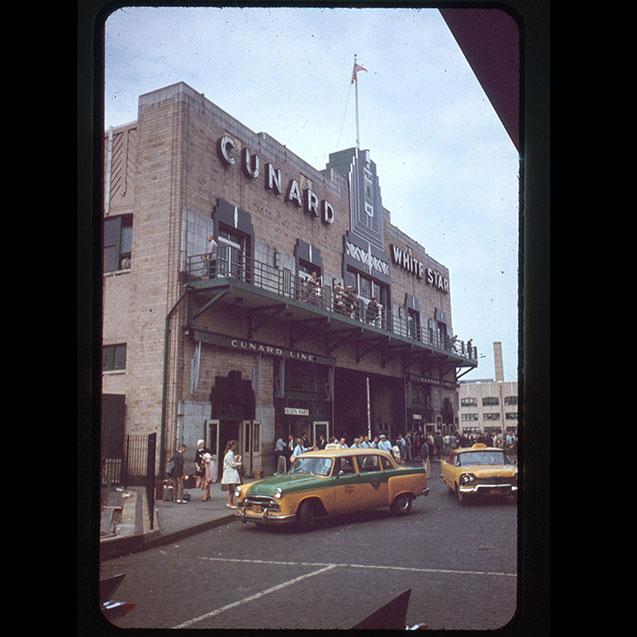

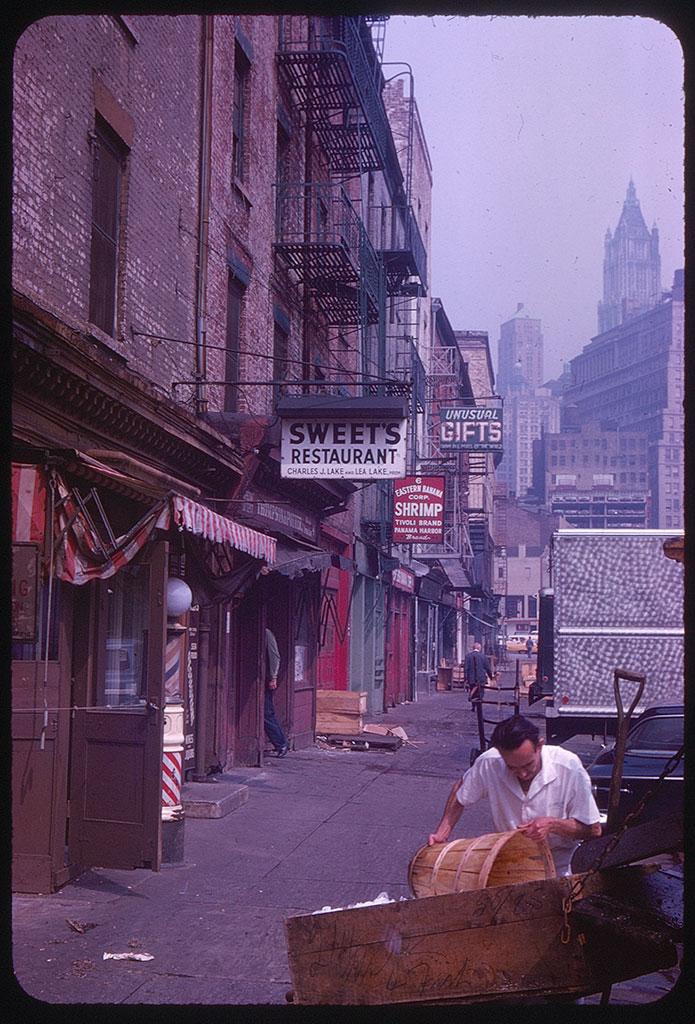

Given the popularity of 35mm slides, maybe it shouldn’t be a surprise that there are over 33,000 slides in the Museum’s collections and archives. A few 35mm slide sets can be found in the accessioned collection, like this set from the 1953 press voyage of the famous transatlantic ocean liner SS Andrea Doria. Donated slides, either accessioned or in the archives, often depict famous vessels in New York Harbor, waterfront work, or street views. When looking for images of New York and harbor from 1960 and onwards, the greatest coverage in the Museum collection can be found in 35mm slides.

Left: “Andrea Doria’s Maiden Voyage Press Party Slides”, 1953. 35mm color film slide. South Street Seaport Museum 2005.021.0022.A-.U

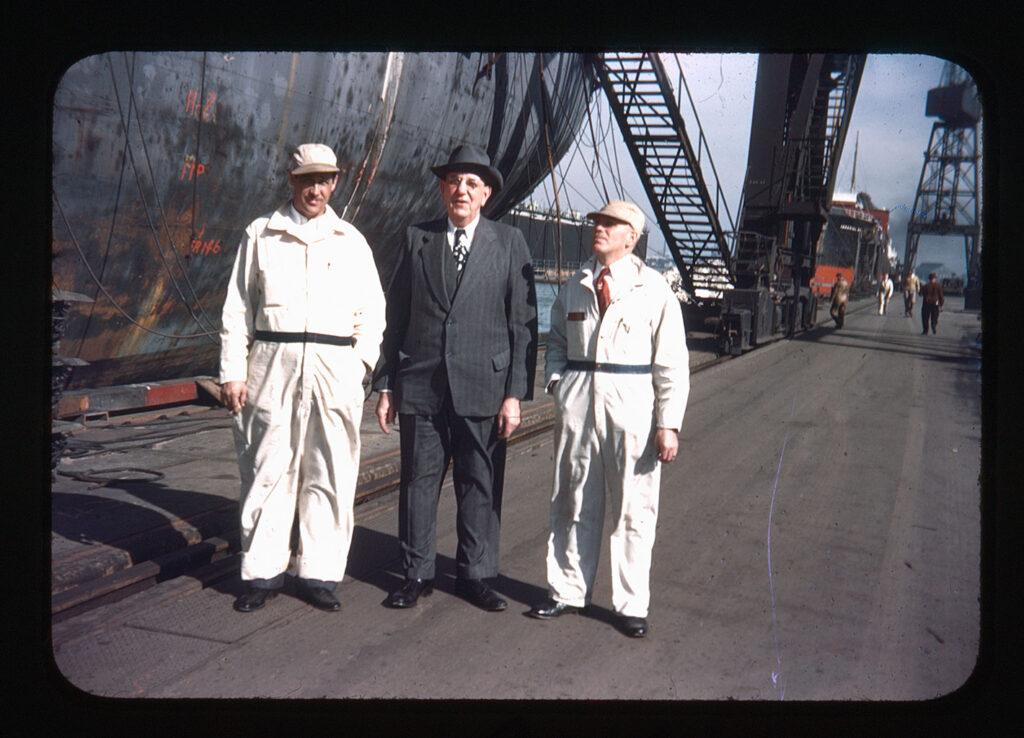

Center: Oscar A.J. Henricksen, photographer. [Men standing on pier beside ship Edward Luckenbach at Baltimore shipyard], 1948. 35mm color film slide. Gift of Joan Henrickson 1994.029

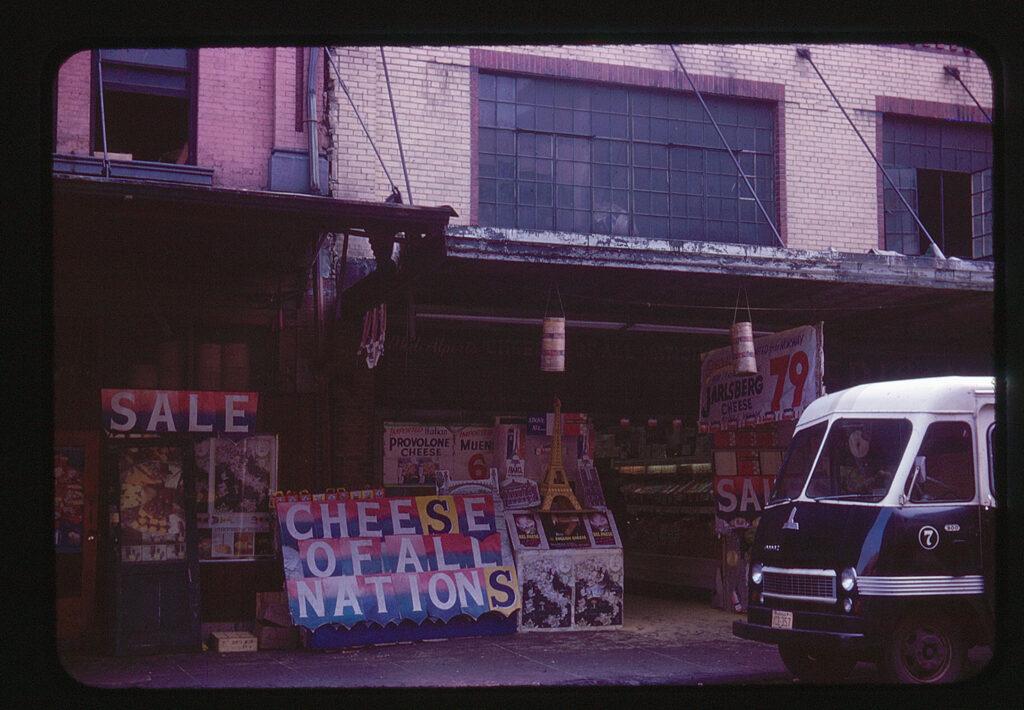

Right: “Alpert’s Cheese Shop, Fulton Street”, June 6, 1963. 35mm color film slide. David Williams Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Archives

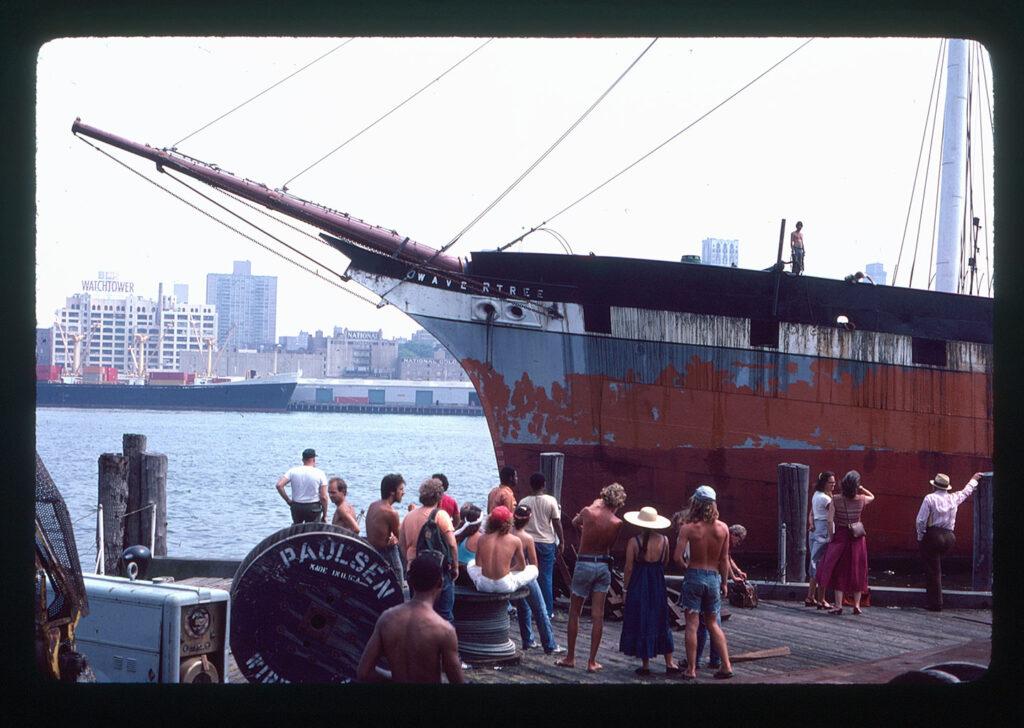

Left: [Volunteers and visitors watching the 1885 tall ship Wavertree from South Street Pier], August 1981. 35mm color film slide. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

Center: [Aerial view of South Street Seaport Historic District from above Brooklyn Bridge], February 1983. 35mm color film slide. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

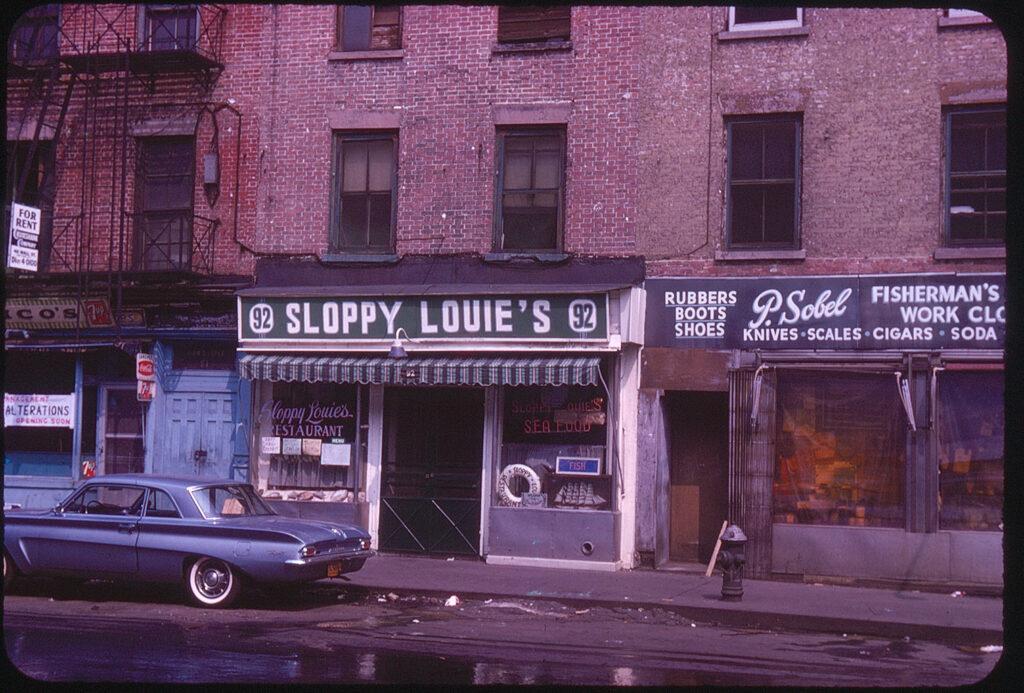

Right: “South Street”, June 6, 1963. 35mm color film slide. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

No part of Manhattan is better represented in the Museum photographic collections than the South Street Seaport Historic District. Aside from images donated to the Museum to document the development and transformation of the seaport district throughout the decades, the majority of the 35mm slides were actually made by Museum staff or volunteers in the course of their preservation, programming, and public engagement work. These slides in the institutional archive are a joy to work with since they are a goldmine of information about past Museum activities. It is one thing to read about an exhibition that took place in 1984 from memos and press releases, and another thing entirely to see what it looked like and how the artworks were displayed. Many slides were made to document preservation efforts on the Museum’s historic fleet and to create photographic records of the artifact collections; due to the high resolution of 35mm slides it is possible to scan these images today in order to examine details not captured in other formats. These slide series are interesting because it seems clear that they were not developed as 35mm slides so that they could be used in any slide show—the choice of the 35mm format must have been due to other advantages like high color fidelity, affordability, ease of storage, etc.

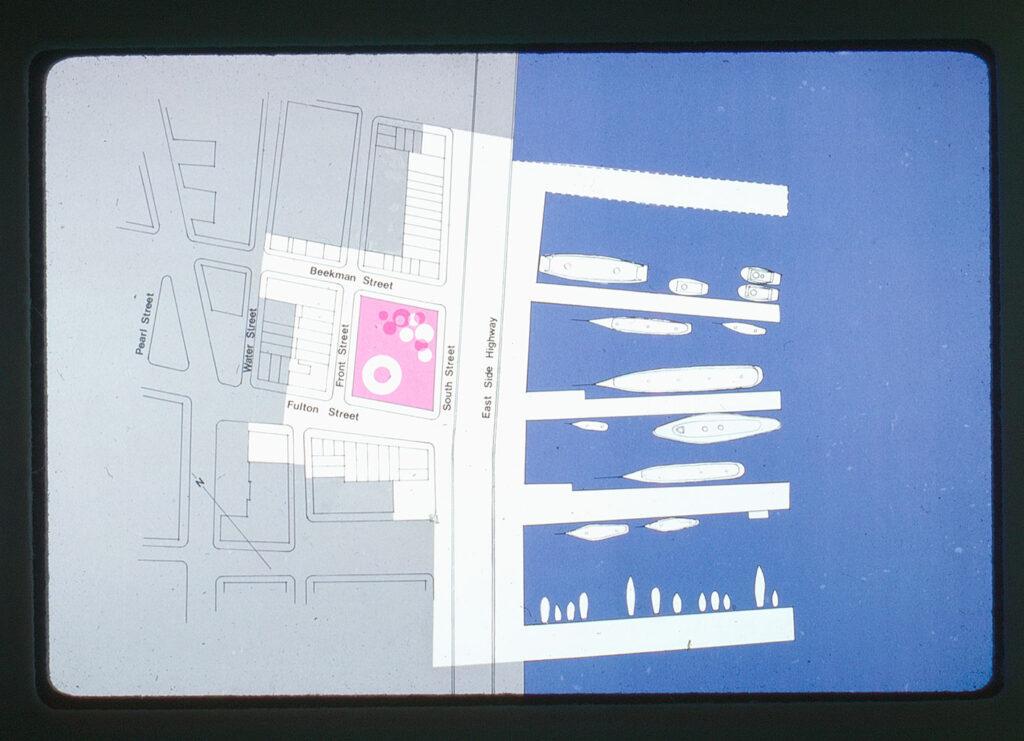

Left: [Map of proposed South Street Seaport Museum piers], September 1967. 35mm color film slide. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

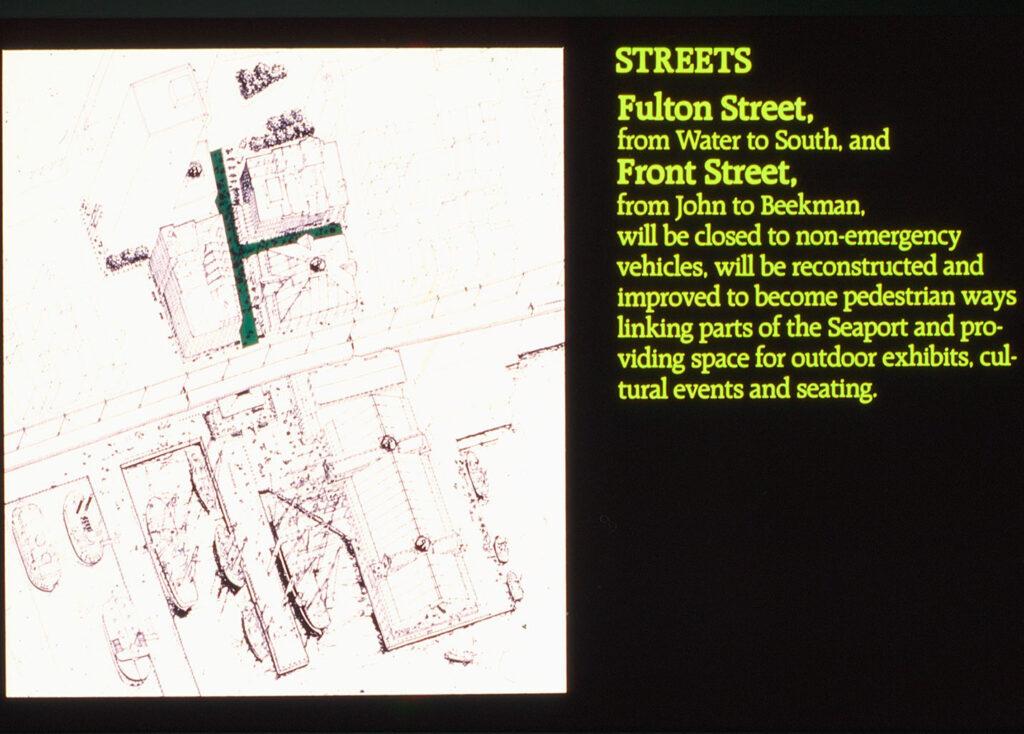

Right: “Streets: Fulton Street from Water to South,…” ca. 1980. 35mm color film slide. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

However, my favorite 35mm slides in the institutional archives are those that are clearly from a slide show. Aside from slide shows developed as educational programming and lecture series, preserved slide shows show how the Museum presented itself and its activities to stakeholders and partners. 35mm slides were used to illustrate funding initiatives, to project proposed capital projects, and otherwise support presenters who may have been pitching the Museum’s mission to everyone from elected officials to the general public.

Another one of the advantages of the 35mm format was that each slide could be added or removed from a slide show “deck” with relative ease. Slides made for one presentation could later be integrated into a new one if needed. This lack of fixed physical order is fantastic for creating slide shows, but can be another hiccup to cataloging slides years later. If a slide is removed from its original series, in what ways can we track how it was created and used?

Caring for 33,000 Slides

For all kinds of collections there are two critical components to stewardship—caring for the physical condition of the object, and caring for the documentation about the object that preserves its historical context and tracks its physical state (location, ownership, condition, etc.) over time. Both of these components are what make cultural heritage accessible and useful; physical care allows for examination and future reexamination of the item while cataloging and digitization lead to searchable documentation and interpretation. The 35mm slides at the Museum present challenges and opportunities to both aspects of care.

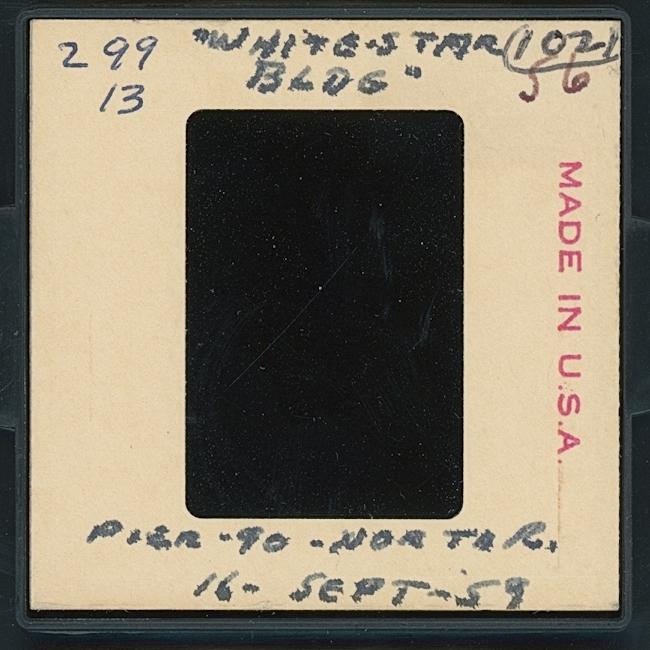

All images: “Pier 90, North River”, September 16, 1963. 35mm color film slide. David Williams Collection, South Street Seaport Museum Archives

Starting with the cataloging side, 35mm slides often have fewer inscriptions than paper-based photographic prints. While it’s pretty easy to take a pencil to the back of a photograph to write down the names of people, places, and other information about the image, slides don’t offer a lot of room for writing. Additionally, if a slide is in a plastic mount, instead of a cardboard mount, pencils and some pens can’t mark them well to begin with. This compounds the issue of describing a slide if it has been separated from other slides from the same photoshoot or slide show. If a slide has no information written on it, and can’t be placed within a larger group, it can be hard to figure out what is depicted and why it was made.

On the flipside, slide mounts can be an important clue to reuniting a slide with its context. The developer and the date are often printed on the mount. In a box of loose mixed slides, it can be efficient to start by sorting by slide mount instead of examining the image of each slide for similar subjects. The importance of the information on slide mounts means that a single slide can need 3 separate scans when being digitized: one for each side of the slide mount and one to capture the actual photograph.

The separation of a slide from its fellows could have happened while at the Museum for several reasons; a collection of slides from a donor may have been scattered when the reference library slides were arranged by subject for researcher accessibility. When slides were donated with 3D objects and artworks, the objects were often accessioned into the permanent collection while the slides and other “archival” mediums were sent to the library with no tracking numbers to associate the slides with the original donation. Sometimes these photographic slides are the only images we have to illustrate the stories surrounding these accessioned objects, while the events pictured in the slides are unrecognizable without knowledge saved in the donation folder. Reuniting these works is critical for both parts of the collection.

“Fulton Street”, June 6, 1963. 35mm color film slide. South Street Seaport Museum Archives

The physical care of 35mm color slides is a topic that may be more meaningful for all of you that have your own collections of slides at home! Though slides were designed to be handled and projected, they can be surprisingly fragile. The chromogenic dyes that create the image on the film are subject to fading. Slides in the Museum collection often have a pink or blue hue to them because the yellow dyes faded first, leaving mainly the magenta and cyan dyes. This fading can be exacerbated by exposure to light and heat, but the dyes will fade overtime even in the best storage conditions. The exact rate of fading depends on several factors, including the brand, type of film base, and the environmental conditions in which the slides are stored. Slides, most notably Kodachrome slides, fade quickly when exposed to intense light and heat for even a short period of time, and so should no longer be shown with a projector if preservation is desired.

The best place to store slides is in a cool, dry, and dark place. Avoid storing photographs in the attic or basement since those areas can have sudden shifts in humidity and temperature, as well as an increased risk of leaks and/or flooding.

The type of storage container can also make a huge difference; an acid-free archival slide box is a good option for large numbers of slides, while polypropylene (a chemically stable plastic) sleeves can reduce damage since the slides can be examined without direct handling.

Example of an archival box for storing 35mm slides

It is important to acknowledge that 35mm slides, like many other film-based formats, have a shelf life, and will eventually fade. One of the best strategies to preserve the photographic image itself can be to scan the slide to create digital images. There are downsides to relying on digital surrogates though; without careful file organization and metadata capture, slides can get even more detached from their original context. Also, digital files need regular management and preservation care or they too can be lost, destroyed, or become so obsolete as to be inaccessible.

Sliding into Obsolescence

Slides remained popular until the rise of digital photography in the 1990s. Declining demand has led to fewer and fewer film manufacturers continuing to produce color slide film, with Kodak discontinuing its last slide duplication stock in 2010. Though many of the people reading this blog post may remember using slide film, and many may still have boxes of treasured family memories saved as slides, other readers have likely never seen a 35mm slide. We are now reaching the age of slides as a largely obsolete format.

Technological obsolescence doesn’t sound like it would be an issue for many museums. Here at the Seaport Museum, for example, we care for all kinds of obsolete technology in the collections—from mercury barometers to kapok-filled lifejackets—while other museums concentrating more on mid-20th century art deal with the preservation of experimental plastic mediums. The 35mm slides present a different challenge because it is one of the formats used by the Museum in its day-to-day operations since its founding 1967. Though the responsibility to care for the artifacts and artworks in the collections is taken as a mandate, it can sometimes be challenging to dedicate resources to caring for the Museum’s institutional memory over time. It can be easy to forget that “everyday” documentation strategies and technologies can quickly become less accessible (or inaccessible) over time. Anyone who has recently tried to retrieve files from a floppy disk (!) may have had this experience first hand.

Thankfully, when it comes to caring for, and cataloging, one of the most common photo formats of the 20th century, we have many resources and case studies from our colleagues at fellow institutions. If you will pardon the pun, I will be “looking through” these for sure!

Additional Reading and Resources

“A History of the Lantern Slide”, UC Arts Digital Lab, University of Canterbury. Accessed May 17, 2023.

“From Luminous Pictures to Transparent Photographs: The Evolution of Techniques for Making Magic Lantern Slides” by Francisco Javier Frutos, The Magic Lantern Gazette, Volume 25, Number 3: Fall 2013.

“Fading Out: The End of 35mm Slide Transparencies”, by Tina Weidner, The Electronic Media Review, Volume Two: 2011-2012.

“Chronology of Film: History of Film from 1889 to Present” Eastman Kodak Company. Accessed May 17, 2023.

“Collection ID Guide: Slides & Transparencies” Preservation Self-Assessment Program, the University of Illinois Libraries. Accessed May 17, 2023.

Research Policies

Conducting research is a vital part of the Seaport Museum’s work. The Museum is actively engaged in a complete inventory of its collections and archives. This ongoing project will improve future public access to the materials in our care and ensure that items are documented and preserved for future generations.